In 1987 Egyptian public television aired the soap opera Sonbol Ba‘d al-Milyon (Sonbol After the Million), a burlesque soap opera of sorts starring the comedian Mohamed Sobhy. It came as a sequel to a popular first part titled The Million Pound Journey, in which Sonbol, the series’ main character, rises up the social ladder, despite his humble origins. Sonbol, played by Sobhy, is an ambitious self-made young man from the Nile Delta who decides to invest his savings by reclaiming desert land in the Sinai Peninsula. Sonbol buys a piece of land from the government and sets out to build a farm. Back in his village Sonbol tries to recruit farmers to work in the land. Anticipating the villagers’ reluctance to move to the desolate Sinai, Sonbol concocts a lie: he tells them that they will be working overseas, in another country called Zarzura. Zarzura is still obviously a desert country, but at least its location abroad intimates a fantasy of an oil-rich Gulf state, which makes it more alluring to the villagers—this was the heyday of Egyptian migration to the Gulf where workers would be expecting to earn multiples of their income back in Egypt. Sonbol succeeds in recruiting the gullible villagers, but he warns them not to speak to any of the locals, since they do not posses “work permits.” In the next scene the plane lands in a small airport in the middle of the desert and as the men walk down the airplane steps, they start chanting hajj incantations, labbayk allahumma labbayk!, believing that they have landed in the precincts of Mecca.

Sonbol’s journey was the first and most prominent representation of Sinai in Egyptian popular culture. There is a reason why Sobhy chose Sinai and the theme of land reclamation as the center of his plot. Five years earlier Egypt had regained control over the Sinai Peninsula in accordance with the 1979 peace treaty with Israel. This was a time during which Sinai was being actively introduced into Egyptian public knowledge as a symbol of pride. The return of the Sinai was presented to the public as a military victory, something that the Mubarak regime was keen on tapping into. On an almost daily basis, national television aired footage of then president Hosni Mubarak raising the Egyptian flag on the last point delivered to Egyptian army units on April 25, 1982. In the background, the voice of Egyptian singer Shadya rang out, “All of Sinai has returned to us, let Egypt rejoice!”

Sinai was the talk of town during those years, but despite all the hype, it was still a terra incognita for most Egyptians. Sinai existed in its national symbolism rather than in its historic or cultural continuity with the mainland. It was hardly an attractive place. It was far away, arid and poorly connected to the mainland. It was uninhabited except for a few nomadic Bedouin tribes with whom most Egyptians never had any contact. Sonbol After The Million epitomizes an encounter with this old-new other: the other land and its other peoples. It played out the old archetype of Egypt versus its age-old desert nemesis. The desert is the averted unknown, and its people, the Bedouins, are quasi-mythical, looked down upon with fear and suspicion. Sonbol symbolizes this troubled relationship (or rather non-relationship) with the land. It was arguably the first time the figure of the Bedouin is presented with some detail, albeit not favorably. Soon after arriving in Sinai, Sonbol is intercepted by a group of Bedouins who accuse him of stealing their fathers’ land. “It is the state’s land. I bought it from the government,” he retorts. The Bedouins do not seem to care. They demand either that he pay them compensation, or leave “to where [he] came from.” Sonbol is unyielding, however: “you left it barren, I came to turn it green,” he replies importantly.

Sonbol meets Ziba, a Bedouin girl from the same clan. She is different, untamed, tough and attractive. Above all she is irrational in her Bedouin habits. “These are our customs and traditions,” was her recurrent rejoinder. She keeps reminding Sonbol that they (Bedouins) are different, something that Sonbol cannot fathom as he goes lampooning her actions. At times the story resembles a minstrel show. Eventually, the two groups reconcile; Sonbol wins the tribe’s confidence, and gains their approval to marry Ziba and settle on the land.

[Screen shot from “Sonbol ba‘d al-milyon.” Screenplay by Ahmed Awad and directed by Ahmad Badr al-Din.]

In 1987 Sinai seemed so distant but Sonbol showed it could be otherwise. He is a man of the frontier, who brings the territory under his dominion, and tames its unruly and recalcitrant population (symbolized by Ziba and her clan). He is the one who reclaims the land in every sense of the word. He is also the entrepreneur, the civilian agent of change, when all that there was hitherto was military. His initial ignorance of the territory was countervailed by his eventual triumph. His ignorance is not an idiosyncrasy but a collective phenomenon. This begs the question: what factors made that part of the country at once a linchpin of national sovereignty and a great unknown? The answer lies in the complex history between the modern Egyptian state and Sinai. Sonbol symbolizes two interconnected processes that would define the relation between Sinai and the mainland since 1982: territorialization and development, both of which took place against a historical backdrop of militarization and exclusion.

Sinai and the Egyptian State

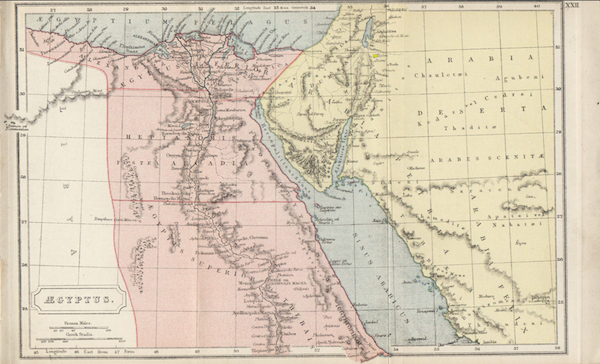

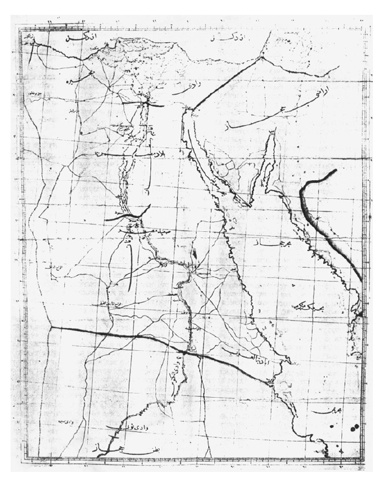

Before we discuss the history of the relationship between Sinai and the Egyptian state we first need to define the geographic entity in question. It is important to differentiate between Sinai as the peninsula that we chart nowadays on the map, and the cultural-historical Sinai.[1] Until roughly the late nineteenth century, the denomination “Sinai” was used to refer to the biblical Mount Sinai. This was not a concrete geographic entity but more of a mythical one, which had always been the subject of speculations of travelers and pilgrims since the third century AD. It came to refer to a loosely defined area in the high mountain massif in the center of the peninsula. Sinai as peninsula, on the other hand, did not come into existence until the late the nineteenth century. Its birth was entangled in territorial conflict among warring geopolitical entities and the making of the modern Egyptian nation state.

During the Ottoman Empire, the northernmost part of the peninsula was administered as part of the province of Egypt. It included areas of urban settlements along the Mediterranean coast such as the villages of al-Arish and Gaza. The rest of the peninsula to the south of the northern coast was administered as part of the Hijaz province. It comprised large swathes of sparsely populated arid terrain extending to the gulfs of Suez and Aqaba, to the southwest and the southeast respectively. The area included the mountainous region traditionally known as the “wilderness of Mount Sinai” at the center of which Monastery of Saint Catherine was situated. The monastery was the oldest institution in the south of the peninsula. A large part of that area was the monastery’s holding, administered in what resembled a medieval feudal demesne where the church sublet tenures of arable land to local Bedouins. Unlike the urban settlements in the north coast, the population of the rest of the peninsula was largely nomadic. Disputes were resolved either according to traditional tribal codes, or, in some cases, by the monastery. Ottoman rule was nominal for the most part, and not surprisingly so, since the area was considered of little military significance. Perhaps the area with most strategic importance was Nekhel in the center of the peninsula, through which the hajj route passed, and where an Ottoman garrison was stationed for the protection of the caravans.

Mohammad Ali Pasha ruled the province of Egypt from 1805 to 1848. During his reign he sought to expand his territory by incorporating other Ottoman lands into the province of Egypt. His first chance came when the Ottoman Sultan Mustafa IV asked Mohammed Ali to send troops to Arabia to crush the nascent Wahhabi movement. The war lasted from 1811 until 1818 and left Muhammad ibn Saud and the Wahhabis defeated, and the territory of Hijaz and Arabia under Mohammad Ali’s rule. Soon the relations between the ambitious governor and the Ottoman sultan deteriorated. Mohammad Ali took up arms against the Ottomans in what is known as the first Egyptian-Ottoman war (1831-1833). The war left most of the Levant, as well as the Sinai Peninsula, under Mohammad Ali`s rule. This situation did not last long, however, as Muhammad Ali was forced to relinquish these territories in 1841 after British and Russian interventions. In return Sultan Abd al-Majid agreed to recognize Mohammad Ali’s permanent rule over Egypt and the Sudan. The agreement also granted Mohammad Ali inheritance rights over these territories, which meant that these provinces would be part of a de facto independent monarchy under the suzerainty of the Ottoman sultan.[2] Abd al-Majid issued a firman demarcating the territories that would belong to Mohammad Ali. The firman defined Egypt as that which existed “within its natural borders” and included a map, signed by the Sultan himself, that marked the eastern border of Egypt from the east of what is now the town of Suez, to the south, to what is known today as Rafah in the northeast.[3] This arrangement left the major part of the Sinai Peninsula outside of the territories of Egypt, which effectively meant a return to the territorial arrangement prior to 1811.

It is unlikely that it took Mohammad Ali long to deliberate whether Sinai should be included in his vilayet of Egypt and the Sudan: compared to other conquered territories, it was a wasteland with very little strategic or economic value. Its insignificance changed radically with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, however. The British, who ruled Egypt as a de facto colony from 1882 on, were keen on keeping a buffer zone between their troops in the Suez Canal and the Turkish troops. According to the 1841 agreement, all the area to east of the Suez Canal was Ottoman territory. In theory, that meant that the Turks could deploy their troops anywhere they wished in the south of Sinai. In practice, however, the closest Ottoman military station was in Aqaba. Tensions between the British and the Ottomans then intensified during the Gulf of Aqaba Crisis in 1906. Lord Cromer, the British governor of Egypt, was wary of Turkish activities in northern Arabia, which he regarded as preludes to Turkish attempts to assert their sovereignty over the peninsula. Lord Cromer sent British troops to Umm Rash-Rash (present day Eilat) to mark what would be the southern point of the Egyptian-Turkish border. The line spread from the east of Aqaba in the south to Rafah in the north, thus incorporating the whole of the Sinai Peninsula as part of Egypt. The situation almost escalated into a full-blown military conflict before Sultan Abd al-Hamid II decided to retreat and accept the British-imposed border.[4] This border continues to demarcate the eastern border of Egypt to this day.

The Ministry of War

1906 was a watershed year in the history of Sinai: it became an entity of geopolitical importance, as a buffer between two empires, with concrete borders. As the territory gained strategic value, it also ushered in a tradition of over-securitization that would last to the present day. Sinai would become first and foremost a military zone. Even pilgrimage, the sole type of civilian activity that had traditionally kept some connection between the territory and Cairo, no longer fulfilled this role after the demise of the old pilgrimage route by land. The old route traversed central Sinai from al-Tur through Nekhel to Aqaba. After the opening of the canal, it was replaced by a safer sea route to the coastal towns of Yanbu‘ and Jiddah in Hijaz. The cessation of this yearly activity consigned the political import of the territory to an exclusively military one.

Traditionally, the hajj was overseen by the Egyptian Ministry of Finance, which oversaw the logistics as well as securing the passage of convoys through the desert. The ministry was in charge of the management of a number of forts in al-Tur and Nekhel. As the route fell into disuse, the Egyptian government (under the control of Lord Cromer) issued a decree in 1885 putting Sinai forts under the responsibility of the Ministry of War. Thus, the director of the Intelligence Department in Cairo became the overall governor of Sinai.[5] When Egypt gained its independence in 1922, ministries significantly reduced the number of their British employees.3 Sinai was an exception. Seen as a strategic depth to the troops stationed by the Suez Canal, British command retained military control over Sinai. It remained so until 1936 when the administration shifted to the Egyptian Ministry of Defense.

Sinai’s territorial history within Ottoman geography as an insignificant wilderness laid the grounds for it to become a contested territory. By the end of the Second World War, the old imperial formation had dissolved. The Ottoman threat had long gone and the British had withdrawn from Sinai to positions along the Suez Canal. However, Sinai continued to be a frontline between two inimical entities, this time two national projects: Egyptian Arabism and Zionism. Sinai would be invaded twice, in 1956 and 1967. Proponents of a Greater Israel repeatedly questioned the region’s belonging to Egypt. They did so interestingly not on the premise that Sinai constituted part of the land of Palestine but rather on the basis of it being a no man’s land. Time after time, contestations of Egyptian sovereignty would go back to the Turco-Egyptian agreement of 1841.[6]

[Map of Egypt. From Atlas Of Ancient And Classical Geography (J M Dent And Sons, 1912)]

Such a continual threat, military as well as discursive, to Egyptian sovereignty might explain the tradition of military over-guarding that Egyptian rulers since president Gamal Abdel Nasser repeatedly adopted vis-à-vis Sinai. As it was a military zone, Egyptians who did not reside in the peninsula needed a special permit to go to Sinai. With no hotels or paved roads, the authorities did not see any reason for citizens from the mainland to want to travel to Sinai.

It is an irony that such a compartmentalization of space came at a time when the boundaries of the modern Egyptian nation state was in formation, and yet in effect led to its further detachment from mainland. For the inhabitants of Sinai, 33,000 in 1958, life continued as usual in spite of all the political turmoil and shifting sovereigns. The Bedouins continued to manage their lives as usual: territorial rights were recognized amongst different clans and disputes adjudicated according to traditional tribal codes. The Monastery of Saint Catherine continues to enjoy gravitas amongst the southern tribes.[7] Relations with the state were minimal, and maintained exclusively through the military intelligence, via a selected chieftain or shaykh.[8] Shaykhs were selected on the basis of their influence in their community and their history of “cooperation,” a strategy that was adapted by the British, the Israelis, and the Egyptians, one after the other. The terms of exchange did not change either: the army unit supplied occasional medical services and food supplies at times of famine, in return for information and allegiance.

Today vestiges of Sinai’s chronically hypersecuritized condition become evident against a backdrop of a worsening security situation in the north of the peninsula. A draft law proposed in 2012 conditioned the launch of any new project in the Sinai on the approval of three entities: the Ministries of Defense, Intelligence, and Interior. In the same year, army chief of staff Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi issued a military decree barring any civilian use of land within six kilometers of the border, while a more controversial decree prohibited Egyptians of dual nationality and those married to non-Egyptians from holding property in Sinai. In the meantime “tribal affairs” continued to be a department within the military intelligence.

From Militarism to Development

Since the second half of the nineteenth century, the relationship between Sinai and the Egyptian state had been conducted in military terms. Sonbol was a break from that tradition: he was a civilian whose encounter with the land was unfettered by any military entity, as far as the story went. He represents a new phase in the relationship between state and periphery. Sonbol sets on his venture—or let us call it his national epic—in the mid-eighties, at a time when Cairo was shifting its outlook on the Sinai. The trauma of the occupation years showed that Sinai’s status as an uninhabited backwater was a strategic weakness and not an asset. The Israeli occupation had proceeded relatively trouble-free; relations with the local Bedouins were untrammeled by anything of the sort that would conjure the latter-day intifadas. It was suggested that if the Israelis had held a referendum on the future of the territory, they would have got a Bedouin approval of Israeli annexation as part of what was known as the Allon Plan. It is impossible to know the truth of this claim, but at least there lingered the perception that Sinai was up for grabs, a slippery territory.

After 1982 the policymakers in Cairo were keen on creating a demographic situation that would safeguard against further challenges to Egyptian sovereignty, especially since Sinai was now demilitarized in accordance with the treaty of Camp David. Furthermore, Hosni Mubarak, who unexpectedly came to power six months before the withdrawal of last Israeli unit, needed a national discourse or project in order to consolidate his presidency. Egypt had been ostracized by the Arab states for its peace accords with Israel and was now in the American camp. The bellicose rhetoric of military triumphalism of yesterday would not have been congenial in a post-Arabist peace era. Mubarak needed a more innocuous, seemingly “apolitical”, national discourse. Development, or tanmiyya in Arabic, was the formula. It referred to the reclamation of land and the encouraging of settlement in the uninhabited desert territories of the country, thus easing the stress on the overpopulated Nile Valley. Although the roots of tanmiyya could be traced back to early days of the republic back in the 1950s, and although it was not specific to Sinai, the troubled history of the peninsula rendered the territory ideal grounds for the development discourse.

From a developmental perspective, the history of Sinai is a concatenation of programs ushered forth by statements of needs and field reports. The first was a report conducted by the firm Dames and Moore between 1980 and 1983 for the Ministry of Housing and Development. There was also the Ministry of Reconstruction Plan of 1981, and the National Plan for the Development of Sinai issued by the Ministry of Planning in 1992. Then came the European Union funded South Sinai Regional Development Program (SSRDP) in 2001 (in which I had the opportunity to participate). Then, following the ousting of Mubarak in 2011, the troubled security situation in North Sinai rekindled the development discourse, and in 2012, the government laid down a draft bill that would lead to the foundation of a ‘permanent’ Sinai development agency (although the details of this are yet to have been finalized until the time of writing).

What these development plans had in common was a commitment to tourism, both as a means for development as well as an end in itself. The overall outlook was geared towards the turning of Sinai into a tourist destination of international import. Large swathes of coastland in the southeast were sold to investors for cheap prices. The Gulf of Aqaba coast was labeled the “Red Sea Riviera.” Each one of these development plans was an update of the previous one. The objectives remained the same, but the numbers changed in two domains: population and hotel room capacity. The number of hotels in South Sinai rose from thirteen in 1989 to 233 in 2007, exceeding the fifty hotels that the Dames and Moore report of 1981 had forecast for the whole of Sinai.[9] Sinai’s population rose to almost half a million in 1989, but did not reach the one million set out in the 1985 plan. In South Sinai, where all of the tourism industry is located, the population was estimated to be around 220,000 in 2013.[10] This is almost over six times the estimated population in 1982: a meager 35,000. Most of this population increase was made up of migrant workers from the Nile Valley seeking employment in the tourism industry and was concentrated in tourist hubs along the Gulf of Aqaba coast. Those areas recorded soaring rates of annual population growth: 7.9 percent in Dahab and nine percent in Nuweiba, while Naama Bay saw a massive 45.7 percent annual population growth.[11]

[Map of Egypt during late Ottoman period. From G. Biger: “The rediscovery of the first geographical political map of Sinai’, in G. Gvirtzman et al. (eds.) Sinai, Tel-Aviv (1987), (Hebrew), pp. 907–12.]

With development came a relative easing of security restrictions in Sinai. The old requirement of a special permit to enter Sinai was lifted. In practice, however, some travellers would find themselves held for questioning or even turned back at army checkpoints before crossing the Suez Canal, without any explanation. It was a social profiling of sorts, just like Sonbol’s ranch, where the villagers were brought in but not allowed to leave, or talk to strangers. True, the territory was now open to citizens, but in a controlled way. Sinai was not to be rendered another part of the country but a refined image of it, branded for export.

Tourism: a Modus Operandi

It is possible to think of the history of tourism and development in Sinai as processes of nationalization. The irony is that tourism capitalized on a primordial social economy that came into existence as a product of the Israeli occupation, something that the scribes of national history would find troubling. Traditionally, tourism in Sinai was limited to religious tourism at Mount Sinai and the Monastery of Saint Catherine. It was sporadic and small in scale. After 1967 the eastern border was open to Israeli and international tourists, expedited by a new road linking the south of Israel to the eastern of part of the peninsula. South Sinai was declared a natural park, operated under the Administration for the Development of South Sinai.[12] The new visitors were not the usual combination of religious tourists and adventurers exploring biblical land. Instead, these were nature-lovers, hipsters, and others who saw Sinai as one of the few remaining true wildernesses of the world. Sinai became the longed-for backyard beyond the slender confines of the Jewish state: a place where they could roam freely without worrying about running into a hostile Arab population.[13]

For the local Bedouins, tourism opened up a new and lucrative frontier of employment. Some worked as guides and organized trekking and camel safari trips. Some worked as drivers. Those who were lucky enough to own land on the beach erected impromptu campsites, or what became known as ‘Bedouin camps.’ These were composed of a handful of thatched huts with basic amenities such as toilets, a kitchen and a fireplace. More importantly, the camp functioned as a station where travel arrangements were made and contacts forged, a point of entry to the landscape.

The advent of grassroots tourism was probably the most important event in the history of modern Sinai. Even the recurrent wars did not leave much of an effect on the community: battles were brief and were limited to few kilometers from the Suez Canal. The Bedouins were never conscripted in the Egyptian army, nor partook in guerrilla warfare. Tourism, on the other hand, had a day-to-day and lasting effect on the community. It opened up the Bedouin landscape to the outside world and was a quick fit in the cultural ecology of the place, with its traditions of hospitality and perpetual peregrination.[14] It introduced a new economy that was not far removed from everyday practice: encampment sites were turned into ‘camping’ sites around the same fireplaces, and instead of moving about herding goats, people could accompany tourists.

This was due to a combination of active planning by the Israelis but also the organic growth of tourism, as a result of the opening of the territory to civilian use for the first time in modern history. Yet from a political perspective, the new economic order occasioned by tourism meant that for many Bedouins, especially the nomads and semi-nomads of the south, the first encounter with the state, as set of services, regulations and citizenry, was that with the Israeli state. This was to raise qualms in Egypt for a long time to come and contributed to the stereotype in Egypt which depicted the Bedouins as traitors and untrustworthy people.

When Egypt regained control over Sinai in 1982, it inherited the burgeoning ecology of tourism, and its tourists. Israeli tourism continued, and even increased. The Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty of 1979 waived entry visas for Israelis traveling from Eilat all the way to the Gulf of Aqaba down to the outskirts of Sharm al-Sheikh and to the west to Mount Sinai. The area was better connected to the south of Israel than to the Egyptian mainland, and corresponded neatly to the area provisioned for unilateral annexation according to the Allon Plan. A whole generation of Bedouins had grown accustomed to the presence of Israeli tourists, who were their main clients and sources of income. Hebrew was spoken alongside Arabic as the lingua franca of tourism and continued to be so well into the early 1990s.

When the Egyptians arrived in 1982 there was apprehension among the Bedouins of what such a change of sovereignty might entail. Mistrust was mutual. When I first traveled to Sinai as a teenager in 1991, the attitude towards Egyptians was still unwelcoming. One was better off traveling with a foreign passport or at least avoiding speaking in Egyptian Arabic at first. Most of the Bedouin camps refused to receive Egyptian tourists, claiming that they did not posses the permits (issued by the Egyptian authorities) that allowed them to host Egyptians. It is doubtful that such a permit ever existed. Perhaps it was a vestige from the pre-tourism days. But it is possible that both camps owners as well the Egyptian authorities thought it would be prudent to keep the Egyptian tourists from their Israeli clients, since any friction between the two, or the intimation of it, would have meant a security as well as financial liability.

The Israeli tourist is the single most important absent-present actor in the Sonbol story. He is Sonbol`s nemesis. He was more popular and better at connecting with the locals than Sonbol, who was, after all, a newcomer. This was what Sonbol, as a good citizen of the frontier was meant to undo. For if Egypt was to celebrate its reinstated sovereignty and assert its victory in the 1973 war, how then could it be that there were more Israelis than Egyptians in Sinai? Moreover, they seemed to be more welcome. Whatever happened in Sinai continued to be a distant affair beyond the bounds of public interest or knowledge for most of the eighties and into the nineties, but things were beginning to change. In 1996, the tabloid Rose al-Yousef published an extended report on Israeli tourism in Dahab, a favored destination for Israeli tourists. The article was an exercise in sensationalism. It portrayed Dahab as a hub for drug addicts, Satan worshippers, degenerate Egyptians, and Israeli operatives. Most shocking was a testimony by a camp operator saying that one Israeli tourist was better than a hundred Egyptian tourists. As usual, fingers were pointed towards the unpopular Camp David Treaty, poised as the Trojan horse that had allowed Sinai to be colonized by Israeli tourists.

Israeli tourism seemed to pose a challenge to the image of the Mubarak regime. The policymakers in Cairo were in a delicate position: they could not simply stop the flow of Israeli tourists by decree since that would compromise the peace treaty. Additionally, the Bedouin economy had grown so dependent on tourism that it would have been unwise to interrupt it, especially since no alternatives were at hand. The problem lay not in the number of Israeli tourists, however, but in the architecture of tourism that favored, by its own design, a certain type of tourism. The crux of the problem was the Bedouin camp model, for a number of reasons. Firstly, it was cheap, hence clients tended to be youth on a budget travelling from Israel. Secondly, the camps relied on word of mouth marketing, which meant that information was more readily available on the Israeli side through the already established clientele than on the Egyptian side. Thirdly, the Bedouin camp was a ‘family business’ contoured along Bedouin norms and forms of organization, which made it difficult to incorporate into the security and surveillance state apparatus, in contrast to the more formal managerial structure of the hotel system. Additionally, these shoestring businesses operated beyond the remit of government fiscal system.

To the Egyptian policymakers, the Bedouin camp was an encumbrance to development, detritus from pre-development times. According to a legend told among Sinai investors, former president Hosni Mubarak was once travelling down the Taba-Nuweiba coast when he pointed to a string of thatched huts by the beach and said to his aides “I want to get rid of all this junk.” Mubarak’s words, unverified as they are, did not mean that the camps should be demolished and their owners kicked out. They meant that Egypt should build ‘real’ hotels, attract more affluent tourists and make profit. That is what development meant: more tourism and everybody would be happy. It is impossible to know if this story is true, but the investors nonetheless agreed. Indeed the landscape was about to change dramatically. The shoestring Bedouin camp model was phased out by an up-market resort model as the Bedouins sold their seaside lands. The number of tourists continued to rise and their nationalities diversified. Now among the tourists, Egyptians are the majority, and permits are a forgotten relic of the past.

The Two Sinais

The most remarkable change, however, was in the social makeup of the South. Now over fifty percent of the population is made of migrant workers and entrepreneurs from the Nile Valley, people like Sonbol and his villagers. The policymakers in Cairo interpret these changes as successful development, and successful Egyptianization for that matter. From the perspective of the Bedouins the conclusion is not as straightforward. Tourism meant employment opportunities. It meant a transition to a more lucrative economy beyond the subsistence livelihood of the past. It meant that parcels of innominate land could now be sold for a fortune. But there also came a downside to tourism development that was inherent to its mode of operation. In contrast with the informal family-business model of the Bedouin camp, the new resort model introduced an ethos of competitive professionalism. By design, this model did not favor young Bedouins who, due to years of neglect, lacked access to education and had often dropped out of their secondary education to work in tourism. While forms of tourism developed, services such as education did not see a parallel development in the forty years since Sinai’s return to Egypt. In time these youths found themselves at a competitive disadvantage with migrant workers from the Nile Valley, who had benefited from better education. Compounded by the perception that Bedouins are ‘free-spirited people who do not like to be bossed around’—a euphemism for undisciplined—employers preferred not to hire Bedouins save for in the most basic jobs. As a result, Bedouins ended up marginalized in the job market.

This is ironic because it was the same community that first adopted tourism and benefited from it forty years ago that was today beset by the inherent contradictions of development. The more the tourism grew, the more disenfranchised the Bedouin community found itself. Today the tourist space of South Sinai is largely Bedouin-free. Most of the hotels and resorts are owned and operated by Egyptians or expatriates with hardly any Bedouin owners. In Sharm El-Sheikh, for example, which is the most active tourist destination in Sinai, there is only one hotel that continues to be owned and run by Bedouins, Ombi Camp in Shark’s Bay. The demographic discrepancy correlates neatly with an economic discrepancy, in which towns that enjoy higher tourism revenues have a smaller Bedouin population. Of the main towns along the Gulf of Aqaba coast the glitzy Sharm El-Sheikh has the least urban concentration of Bedouins, while the inconspicuous Nuweiba has the highest.

So where did the Bedouins go? They moved inland. The hinterlands were an exclusively Bedouin country, with the majority living in informal encampments close to subterranean water sources. With the exception of Mount Sinai area, this is a tourist-less country (which also means it is development-less country). Government presence is minimal and sporadic. Economic activity revolves around the cultivation of a cannabis plant, banjo, or the more lucrative opium poppy, and the smuggling of asylum seekers across the Israeli border. Notwithstanding its illicit economy, this is a poverty-ridden area.

[Screen shot from “Sonbol ba‘d al-milyon.” Screenplay by Ahmed Awad and directed by Ahmad Badr al-Din.]

Historically the hinterland valleys were the real homestead of the community. They were more populous than the coastland, which owes its relatively recent development to tourism. After years of such development, the littoral space has superseded the inland in importance. Now the two spaces are more markedly disparate and distant than ever before. Touristic development resulted not only in the separation of the two spaces but in the compartmentalization of each. This is the story of two Sinais, whose difference can be plotted not only in terms of income but also in ethnic and cultural terms: one is exclusively Bedouin while the other excludes Bedouins. One is a state space, where the security apparatus is always present, while in the other, traditional forms of governance still dominate and the state’s presence is nominal and often unwelcome.

Tourism was meant to be a tool for inclusion, for incorporation into the state’s machinery of security and governance. For the Bedouin community the policies of tourism development have been centrifugal and exclusionary. The state’s attempt to dismantle the old ecology of tourism and replace it with a mass-tourism model was successful in quantitative terms, but detrimental to the community. Excessive government regulations such as the limitations imposed upon overnight safaris, for instance, tended to favor large companies, but cripple small operations such as those run by the Bedouins.

In the hinterland, the government habitually turned a blind eye to the illicit economy, as long as it did not take place in, or affect, the touristic areas. In other words, a lawless hinterland was permitted in return for a peaceful coast. This is of course a shortsighted policy. An underground illicit economy engenders endemic violence, and corruption that pays it off. Conflict with the state apparatus is usually inevitable in the long run. In this regard, the insurgency in northern Sinai is not irrelevant, despite the fact that the North does not have a parallel history to the South in terms of development and tourism. Since Israel imposed its blockade on the Gaza Strip in 2007, the area has been dependent on smuggled goods, both legal and illicit, from the Egyptian side. This has engendered a fulminant underground economy in the North, which the Mubarak regime chose to ignore. The North might be a special case due to its bordering of Gaza. One could argue that much of the insurgency that erupted since 2011 is more of a reaction against the army’s attempt to disrupt the underground economy (by destroying the tunnels) than an ideologically motivated enterprise as it is usually presented. However, the North also shares much with the rest of the hinterlands of the peninsula: an underground social economy undergirded by tribal social formation and compounded by long history of marginalization and poverty. This is a time bomb, even without taking into account the complex politics on the other side of the border. The situation in the North is a reflection of an endemic malaise that is not limited to the border region. Tourism, in this regard, has only been palliative.

[1] See Ahmad Hosni, “Go Down, Moses: Tourism, Space and Ideology, Ibraaz 1, and “Faulkner in Sinai,” Photographies Vol. 6, No. 2 (2013), 243-258.

[2] Gideon Biger, Boundaries of Modern Palestine (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), 21-27.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 28-40.

[5] Karim Zaki-Kahlil, “British Sinai: its Geopolitical Significance in the Middle East and its Strategic Role in British Colonial Policy” (PhD diss., Durham University, 1998), 108 -113.

[6] See for example Shmuel Katz, Battleground: Fact and Fantasy in Palestine (Taylor Productions, 2002), 70.

[7] See Zaki-Kahlil, 166.

[8] See Martin Ira Glassner, “The Bedouin of South Sinai Under Israeli Occupation,” Geographical Review Vol. 64, No. 1 (1974), 31.

[9] PA Consulting Group, Sustainable Tourism Development Plan for South Sinai 2007 – 2017 Executive Summary, EuropeAid/122290/D/SV/EGEurope Aid, (2008), 3.

[10] Egyptian Ministry of State for Environmental Affairs, Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency: South Sinai Environment and Development Profile, SEAM (2005), 13. This is a projected number based on the census of 1996.

[11] Ibid., 9; The Advisory Committee for Reconstruction, Ministry of Development, Arab Republic of Egypt, Sinai Development Study: Phase I, Final Report, Vol. II Managing Sinai’s Development, prepared by Dames & Moore in association with Industrial Development Programs (1985), 21.

[13] See Waleed Hazbun, Beaches, Ruins and Resorts: The Politics of Tourism in the Arab World (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

[14] See Hosni “Faulkner in Sinai,” 243-258.

![[Screen shot from “Sonbol ba‘d al-milyon.” Screenplay by Ahmed Awad and directed by Ahmad Badr al-Din.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/4.jpg)